Get Started, Part 2: Containers

Estimated reading time: 13 minutesPrerequisites

- Install Docker version 1.13 or higher.

- Read the orientation in Part 1.

-

Give your environment a quick test run to make sure you’re all set up:

docker run hello-world

Introduction

It’s time to begin building an app the Docker way. We’ll start at the bottom of the hierarchy of such an app, which is a container, which we cover on this page. Above this level is a service, which defines how containers behave in production, covered in Part 3. Finally, at the top level is the stack, defining the interactions of all the services, covered in Part 5.

- Stack

- Services

- Container (you are here)

Your new development environment

In the past, if you were to start writing a Python app, your first order of business was to install a Python runtime onto your machine. But, that creates a situation where the environment on your machine has to be just so in order for your app to run as expected; ditto for the server that runs your app.

With Docker, you can just grab a portable Python runtime as an image, no installation necessary. Then, your build can include the base Python image right alongside your app code, ensuring that your app, its dependencies, and the runtime, all travel together.

These portable images are defined by something called a Dockerfile.

Define a container with a Dockerfile

Dockerfile will define what goes on in the environment inside your

container. Access to resources like networking interfaces and disk drives is

virtualized inside this environment, which is isolated from the rest of your

system, so you have to map ports to the outside world, and

be specific about what files you want to “copy in” to that environment. However,

after doing that, you can expect that the build of your app defined in this

Dockerfile will behave exactly the same wherever it runs.

Dockerfile

Create an empty directory. Change directories (cd) into the new directory,

create a file called Dockerfile, copy-and-paste the following content into

that file, and save it. Take note of the comments that explain each statement in

your new Dockerfile.

# Use an official Python runtime as a parent image

FROM python:2.7-slim

# Set the working directory to /app

WORKDIR /app

# Copy the current directory contents into the container at /app

ADD . /app

# Install any needed packages specified in requirements.txt

RUN pip install --trusted-host pypi.python.org -r requirements.txt

# Make port 80 available to the world outside this container

EXPOSE 80

# Define environment variable

ENV NAME World

# Run app.py when the container launches

CMD ["python", "app.py"]

Are you behind a proxy server?

Proxy servers can block connections to your web app once it’s up and running. If you are behind a proxy server, add the following lines to your Dockerfile, using the

ENVcommand to specify the host and port for your proxy servers:# Set proxy server, replace host:port with values for your servers ENV http_proxy host:port ENV https_proxy host:port

This Dockerfile refers to a couple of files we haven’t created yet, namely

app.py and requirements.txt. Let’s create those next.

The app itself

Create two more files, requirements.txt and app.py, and put them in the same

folder with the Dockerfile. This completes our app, which as you can see is

quite simple. When the above Dockerfile is built into an image, app.py and

requirements.txt will be present because of that Dockerfile’s ADD command,

and the output from app.py will be accessible over HTTP thanks to the EXPOSE

command.

requirements.txt

Flask

Redis

app.py

from flask import Flask

from redis import Redis, RedisError

import os

import socket

# Connect to Redis

redis = Redis(host="redis", db=0, socket_connect_timeout=2, socket_timeout=2)

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def hello():

try:

visits = redis.incr("counter")

except RedisError:

visits = "<i>cannot connect to Redis, counter disabled</i>"

html = "<h3>Hello {name}!</h3>" \

"<b>Hostname:</b> {hostname}<br/>" \

"<b>Visits:</b> {visits}"

return html.format(name=os.getenv("NAME", "world"), hostname=socket.gethostname(), visits=visits)

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=80)

Now we see that pip install -r requirements.txt installs the Flask and Redis

libraries for Python, and the app prints the environment variable NAME, as

well as the output of a call to socket.gethostname(). Finally, because Redis

isn’t running (as we’ve only installed the Python library, and not Redis

itself), we should expect that the attempt to use it here will fail and produce

the error message.

Note: Accessing the name of the host when inside a container retrieves the container ID, which is like the process ID for a running executable.

That’s it! You don’t need Python or anything in requirements.txt on your

system, nor will building or running this image install them on your system. It

doesn’t seem like you’ve really set up an environment with Python and Flask, but

you have.

Build the app

We are ready to build the app. Make sure you are still at the top level of your new directory. Here’s what ls should show:

$ ls

Dockerfile app.py requirements.txt

Now run the build command. This creates a Docker image, which we’re going to

tag using -t so it has a friendly name.

docker build -t friendlyhello .

Where is your built image? It’s in your machine’s local Docker image registry:

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID

friendlyhello latest 326387cea398

Tip: You can use the commands

docker imagesor the newerdocker image lslist images. They give you the same output.

Run the app

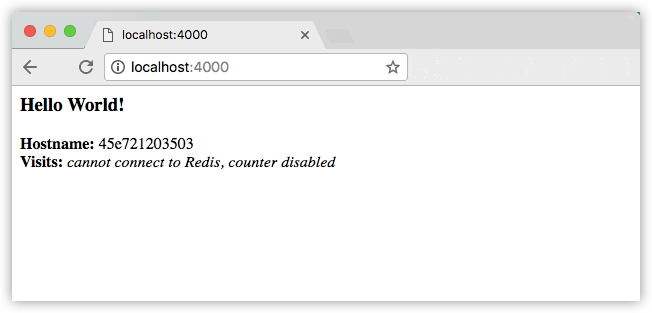

Run the app, mapping your machine’s port 4000 to the container’s published port

80 using -p:

docker run -p 4000:80 friendlyhello

You should see a message that Python is serving your app at http://0.0.0.0:80.

But that message is coming from inside the container, which doesn’t know you

mapped port 80 of that container to 4000, making the correct URL

http://localhost:4000.

Go to that URL in a web browser to see the display content served up on a web page, including “Hello World” text, the container ID, and the Redis error message.

You can also use the curl command in a shell to view the same content.

$ curl http://localhost:4000

<h3>Hello World!</h3><b>Hostname:</b> 8fc990912a14<br/><b>Visits:</b> <i>cannot connect to Redis, counter disabled</i>

This port remapping of 4000:80 is to demonstrate the difference

between what you EXPOSE within the Dockerfile, and what you publish using

docker run -p. In later steps, we’ll just map port 80 on the host to port 80

in the container and use http://localhost.

Hit CTRL+C in your terminal to quit.

On Windows, explicitly stop the container

On Windows systems,

CTRL+Cdoes not stop the container. So, first typeCTRL+Cto get the prompt back (or open another shell), then typedocker container lsto list the running containers, followed bydocker container stop <Container NAME or ID>to stop the container. Otherwise, you’ll get an error response from the daemon when you try to re-run the container in the next step.

Now let’s run the app in the background, in detached mode:

docker run -d -p 4000:80 friendlyhello

You get the long container ID for your app and then are kicked back to your

terminal. Your container is running in the background. You can also see the

abbreviated container ID with docker container ls (and both work interchangeably when

running commands):

$ docker container ls

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED

1fa4ab2cf395 friendlyhello "python app.py" 28 seconds ago

You’ll see that CONTAINER ID matches what’s on http://localhost:4000.

Now use docker container stop to end the process, using the CONTAINER ID, like so:

docker container stop 1fa4ab2cf395

Share your image

To demonstrate the portability of what we just created, let’s upload our built image and run it somewhere else. After all, you’ll need to learn how to push to registries when you want to deploy containers to production.

A registry is a collection of repositories, and a repository is a collection of

images—sort of like a GitHub repository, except the code is already built.

An account on a registry can create many repositories. The docker CLI uses

Docker’s public registry by default.

Note: We’ll be using Docker’s public registry here just because it’s free and pre-configured, but there are many public ones to choose from, and you can even set up your own private registry using Docker Trusted Registry.

Log in with your Docker ID

If you don’t have a Docker account, sign up for one at cloud.docker.com. Make note of your username.

Log in to the Docker public registry on your local machine.

$ docker login

Tag the image

The notation for associating a local image with a repository on a registry is

username/repository:tag. The tag is optional, but recommended, since it is

the mechanism that registries use to give Docker images a version. Give the

repository and tag meaningful names for the context, such as

get-started:part2. This will put the image in the get-started repository and

tag it as part2.

Now, put it all together to tag the image. Run docker tag image with your

username, repository, and tag names so that the image will upload to your

desired destination. The syntax of the command is:

docker tag image username/repository:tag

For example:

docker tag friendlyhello john/get-started:part2

Run docker images to see your newly

tagged image. (You can also use docker image ls.)

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

friendlyhello latest d9e555c53008 3 minutes ago 195MB

john/get-started part2 d9e555c53008 3 minutes ago 195MB

python 2.7-slim 1c7128a655f6 5 days ago 183MB

...

Publish the image

Upload your tagged image to the repository:

docker push username/repository:tag

Once complete, the results of this upload are publicly available. If you log in to Docker Hub, you will see the new image there, with its pull command.

Pull and run the image from the remote repository

From now on, you can use docker run and run your app on any machine with this

command:

docker run -p 4000:80 username/repository:tag

If the image isn’t available locally on the machine, Docker will pull it from the repository.

$ docker run -p 4000:80 john/get-started:part2

Unable to find image 'john/get-started:part2' locally

part2: Pulling from john/get-started

10a267c67f42: Already exists

f68a39a6a5e4: Already exists

9beaffc0cf19: Already exists

3c1fe835fb6b: Already exists

4c9f1fa8fcb8: Already exists

ee7d8f576a14: Already exists

fbccdcced46e: Already exists

Digest: sha256:0601c866aab2adcc6498200efd0f754037e909e5fd42069adeff72d1e2439068

Status: Downloaded newer image for john/get-started:part2

* Running on http://0.0.0.0:80/ (Press CTRL+C to quit)

Note: If you don’t specify the

:tagportion of these commands, the tag of:latestwill be assumed, both when you build and when you run images. Docker will use the last version of the image that ran without a tag specified (not necessarily the most recent image).

No matter where docker run executes, it pulls your image, along with Python

and all the dependencies from requirements.txt, and runs your code. It all

travels together in a neat little package, and the host machine doesn’t have to

install anything but Docker to run it.

Conclusion of part two

That’s all for this page. In the next section, we will learn how to scale our application by running this container in a service.

Recap and cheat sheet (optional)

Here’s a terminal recording of what was covered on this page:

Here is a list of the basic Docker commands from this page, and some related ones if you’d like to explore a bit before moving on.

docker build -t friendlyname . # Create image using this directory's Dockerfile

docker run -p 4000:80 friendlyname # Run "friendlyname" mapping port 4000 to 80

docker run -d -p 4000:80 friendlyname # Same thing, but in detached mode

docker container ls # List all running containers

docker container ls -a # List all containers, even those not running

docker container stop <hash> # Gracefully stop the specified container

docker container kill <hash> # Force shutdown of the specified container

docker container rm <hash> # Remove specified container from this machine

docker container rm $(docker container ls -a -q) # Remove all containers

docker image ls -a # List all images on this machine

docker image rm <image id> # Remove specified image from this machine

docker image rm $(docker image ls -a -q) # Remove all images from this machine

docker login # Log in this CLI session using your Docker credentials

docker tag <image> username/repository:tag # Tag <image> for upload to registry

docker push username/repository:tag # Upload tagged image to registry

docker run username/repository:tag # Run image from a registry